2018年7月19日 星期四

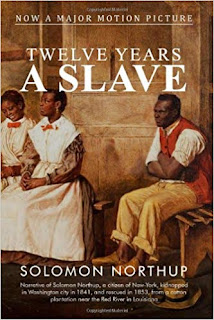

"Twelve Years a Slave" by Solomon Northup (1853)

"The hands are required to be in the cotton field as soon as it is light in the morning, and, with the exception of ten or fifteen minutes, which is given them at noon to swallow their allowance of cold bacon, they are not permitted to be a moment idle until it is too dark to see, and when the moon is full, they often times labor till the middle of the night. They do not dare to stop even at dinner time, nor return to the quarters, however late it be, until the order to halt is given by the driver."

I think it's only fair to state that the contents of this book were dictated by Solomon Northup to another man, David Wilson. Wilson was a lawyer and politician active in the abolitionist cause.

This aside, the historical record agrees with everything set down in the book. Solomon Northup, a native of New York, was indeed abducted by slave traders while in Washington D.C., and he spent the next 12 years as a slave on a cotton plantation in Louisiana. In Twelve Years a Slave he offers a harrowing account of his years in bondage, and I have no doubt that his narrative (and similar books) served to widen the gulf between the northern and southern states prior to the Civil War.

But I have to be honest here and say that reading Twelve Years a Slave was a real chore for me. It's not that I disagree with anything recorded in this book, and it's not that I find fault with the overall account of Northup's troubles. It's just that it's written in the style of a pamphlet, and its sole purpose is the conversion of the reader to the abolitionist point of view. This means that the pace of the book is slow, that the prose is labored, and that the author often reaches his conclusions in the most roundabout way.

Despite its short length, Twelve Years a Slave is far from light reading. And not being a work of fiction, it goes out of its way to establish the factual nature of the events it describes. The working of cotton plantations and sugar cane refineries are detailed for the edification of 19th century northern readers who wouldn't have been familiar with such things, and some of the more human elements, which might have made the book more accessible to modern readers, are discarded for the sake of legal "proofs" which underpin the veracity of the story.

You would, in other words, be far better served by watching the movie. Nothing in this book absent from that movie, save for a court case that goes nowhere and helps no one.

Related Entries:

"Gone with the Wind" by Margaret Mitchell (1936)

"Papillon" by Henri Charriere (1970)

"The Underground Railroad" by Coulson Whitehead (2016)

"Crow Killer" by Raymond W. Thorp and Robert Bunker (1969)

標籤:

northup,

review,

solomon,

twelve years a slave

位置:

台灣

訂閱:

張貼留言 (Atom)

沒有留言:

張貼留言